Many coaches working in English-speaking environments were born and raised in another cultural and/or linguistic environment. And the reverse is also true, especially in Toronto, where roughly 50% of the population was not born in Canada. Given that we all tend to make assumptions and draw conclusions based on our own conditioning and experience, there are many things to consider when working with someone who has grown up in a different culture, speaking a different language.

Despite how well one speaks the local language or seems to understand the culture, there are always gaps which lead to misunderstanding and misinterpretations. In this article I want to focus on behaviours related to concepts of time and space. Consider the following:

While adopting my daughter in Peru, I was being assessed by a psychiatrist who was asking a lot of questions. I was slow putting my thoughts together, having just arrived in a Spanish environment. Each time, as I was completing my response, he would ask me the next question. This happened repeatedly and it was beginning to feel like an interrogation. I was stressed and irritated.

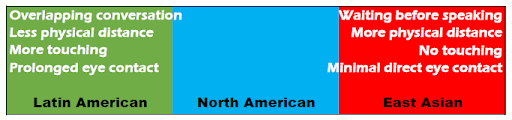

I was aware that, socially, Latin Americans often begin to speak before you have completed your thoughts. This is also common in North America among family members and friends in social settings. In fact, the closer people are, the more our words cross over. But for English-speaking Canadians, it is considered rude to “interrupt” in a professional environment.

When I tell this story to Latin Americans, they often start to smile. “It’s what we often do, start to speak before the other person is finished. Even in the workplace.” Why the difference? It is related to the degree of intimacy permitted by the culture.

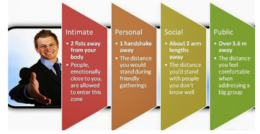

In this case, we are talking about turn-taking in conversation. As a rule, the more social distance we put between ourselves and the other person, the more time we wait and vice versa. This distance can be related to many things – the relative level of authority or hierarchy, how well you know someone, the social setting, the culture and personality of the individual, etc. Making a huge generalization as an example, Latin American people tend to express more intimacy towards each other than North Americans do, who in turn tend to express more intimacy than East Asians do.

Culturally-appropriate behaviour is not static – it moves over time and through changes in society. We must also adjust for the individual sense of appropriate behaviour which may not be within the parameters of what is allowed culturally although generally it is, albeit sometimes at one extreme. The range of culturally appropriate behaviour can overlap between cultures and individuals but the gross generalizations still stand.

Turn-taking is related to timing. But we can extend our generalization to aspects of space and physicality also which include distance, touch and eye contact.

Assuming we are observing a similar environment, for example a business setting, we can make a similar generalization:

The problem here is how we interpret the behaviour. For example, I was in a reception area and the woman attending looked at me directly for more than the usual time. My impression was that she was exceptionally warm. Later I considered, if I had been interested sexually, I would have thought she was flirting with me. In North America, we reserve that long, direct eye contact for close and intimate partners. The stereotype of the Latin lover comes from the North American interpretation of the increased touch, the closer stance and the longer eye contact. A Latin American knows how to interpret these behaviours.

In contrast, I became friends with a young Chinese professor in residence in Toronto. She told me that when she left her country for the year-long stay in Canada, she bowed to her husband at the airport – no hugging, no touching.

Much of the initial interest to study cultural differences was born in the 50s when Americans started to do business in Japan. In one story, while negotiating, the American quoted a price and waited for a response. Expecting an immediate one, he decided that the silence meant they thought the price was too high. So, he dropped it by 10%. Again silence, and again another 10% drop. After the third discount he got frustrated and waited. Finally, after a silence, they agreed to his offer. Upon reflection, he later realized that they might very likely have agreed to the initial price, had he waited long enough.

These stories are endless. But they point to the importance of refraining from judgments regarding the meaning of such interactions. It is easy to get angry or upset if we feel a client is flirting with us. It is easy to interpret silence as timidity or insecurity. It is easy to judge someone who violates the accepted North American distance as being fearful – too far – or overly intimate – too close. While COVID is seriously changing many of these expectations, the basics concepts remain the same.

————–

It would be great to hear any stories, observations or thoughts related to social interactions between cultures, in particular those related to time and space.